Explore the potential of a simple finger-prick blood test for toddlers, identifying the risk of type 1 diabetes. Learn about a UK trial aiming to revolutionize early detection, delay onset, and prevent severe complications, providing crucial insights into this groundbreaking screening method.

Researchers are exploring the possibility of using a simple finger-prick test in toddlers as young as two to gauge their risk of developing type 1 diabetes. The trial, involving 20,000 children in the UK, aims to assess the efficacy of this screening method.

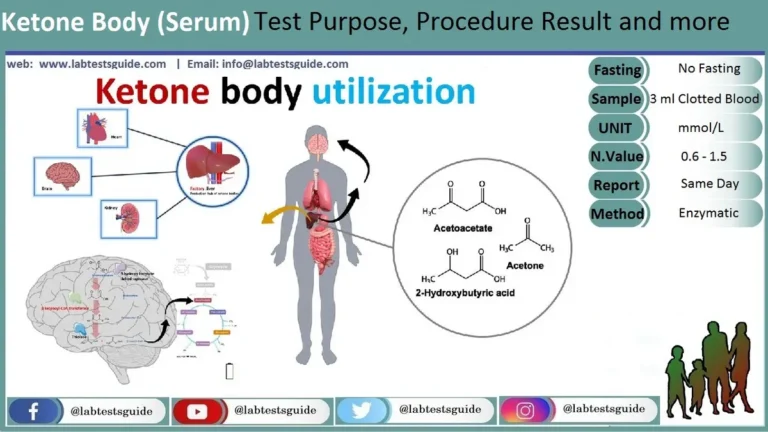

Type 1 diabetes affects approximately one in 500 children in the UK, with a concerning 25% receiving a diagnosis only when admitted to hospitals due to a severe diabetic condition known as ketoacidosis. This critical situation arises when the blood becomes toxic and can prove fatal.

The trial seeks to introduce immunotherapy treatment, specifically teplizumab, to toddlers identified as at risk, potentially delaying the onset of diabetes. Experts stress that delaying the development of type 1 diabetes could significantly lower the chances of severe complications such as limb amputations, heart disease, kidney issues, and blindness.

Professor Parth Narendran of the University of Birmingham leads this screening trial, emphasizing the potential benefits: “Screening has shown promise in reducing diabetic crises, improving glucose control, and mental well-being. This could result in cost savings for the NHS.”

Furthermore, the trial aims to identify rogue immune proteins called autoantibodies. These proteins attack the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, leading to diabetes.

The process involves a straightforward finger-prick test, akin to the heel-prick test conducted on newborns to screen for various health conditions. Children testing positive for multiple autoantibodies will undergo further assessments to determine their risk of developing type 1 diabetes.

Professor Colin Dayan from Cardiff University, speaking at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) conference, highlighted that children with multiple types of autoantibodies were significantly more likely to develop type 1 diabetes within 15 years.

While the finger-prick test isn’t presently part of the newborn screening, Professor Narendran suggests the possibility of incorporating a genetic test in newborn programs to identify high-risk individuals for future antibody testing at age two or three.

Diabetes charities, including JDRF and Diabetes UK, are funding the trial, hoping the results will support the implementation of widespread screening for children.

Experts at the EASD conference emphasized that type 1 diabetes progresses gradually, suggesting that early identification through screening could predict the need for insulin and prevent life-threatening diabetic episodes.

Professor Narendran also expressed openness to recruiting younger children, aiming to potentially extend the screening to include two-year-olds based on evolving research and parental interest.

The incidence of type 1 diabetes in children has been rising steadily, with a sharp increase observed during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, prompting investigations into a possible link between the infection and the onset of diabetes.

Source: Routine finger-prick blood test could be used to identify toddlers’ risk of type 1 diabetes

Possible References Used